Introduction to the Sustainable Development Goals

Lesson 1: Information on the SDGs

Lesson 1.1. Background and reporting

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) Member states, adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the aim of which is to serve as a guideline for the conduct that will help us preserve the planet and its inhabitants. At its core lie the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are the “the call for action” to all countries around the globe. Based on the main issues that we all face on both a local and global scale, the Goals aim at both prevention and mitigation of existing risks.

The process that ended up with the creation and publication of the SDGs already started in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Brazil, where the focus on the decisions was on improving human lives and environmental protection. Eight years later the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were agreed upon during the Millennium Summit. The collaboration between states that followed had a number of key stages throughout the years, with the establishment of working groups, outcome documents and others that set -out targets, desired outcomes and actions that will help reach the aforementioned. “2015 was a landmark year for multilateralism and international policy shaping, with the adoption of several major agreements:

The UN provides support, guidance and capacity building for the SDGs and their implementation through the Division for Sustainable Development Goals (DSDG). The “science-policy interface” is a major point in understanding and implementing science whilst intertwining with all the desired outcomes. This is done via the so-called Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR). In 2016, it was agreed that the report will be published every 4 years, and in 2023 the second report is to be published as we reach the halfway point. Annual progress report on the SDGS is also published by the UN.

Lesson 1.2. The SDGs in a nutshell

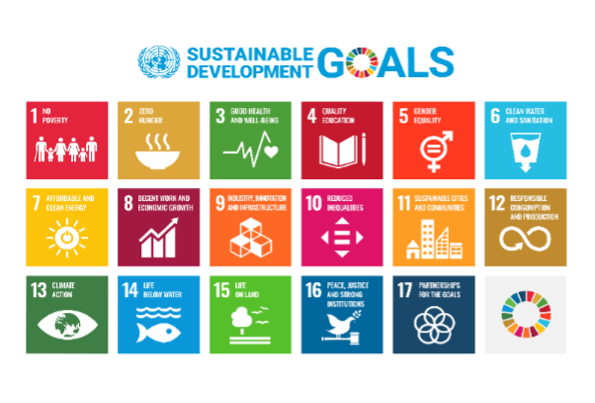

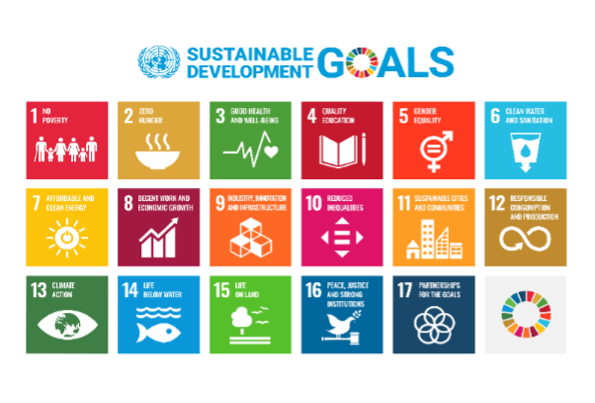

The Sustainable Development goals, also known as SDGs or Global goals were adopted in 2015 and have an end date-2030. They consist of 17 separate, but yet intertwined and mutually dependent goals and corresponding targets. Each action for one goal can have either a direct or indirect effect on another, and often said actions have to be multifaceted, well planned and executed. The goals consist of 169 targets overall. Countries have committed to prioritize progress for those who are furthest behind. Again, it is important to note, that even though they are agreed upon by UN member states, they only serve as a guideline, not a law. Even though there is legislative framework that either underpins or supports many of the targets, it is not consistent or universally applied, but it is rather on a country-by-country basis. This is also one of the main criticisms of the SDGs, which will be discussed in Lesson 2.

Image from UN SDG website

Image from UN SDG websiteThe Goals themselves are as follows:

Goal 1. No Poverty (7 targets)

Goal 2. Zero Hunger (8 targets)

Goal 3. Good health and well-being (13 targets)

Goal 4. Quality education (10 targets)

Goal 5. Gender Equality (9 targets)

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation8 targets)

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy (5 targets)

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth (12 targets)

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure (8 targets)

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities (10 targets)

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities (10 targets)

Goal 12. Responsible production and consumption (11 targets)

Goal 13. Climate action (5 targets)

Goal 14. Life below water (10 targets)

Goal 15. Life on land (12 targets)

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions (12 targets)

Goal 17. Partnership for the goals (19 targets)

For more detailed information, the following formal page regarding the SDGs should be reviewed: https://sdgs.un.org/#goal_section

Lesson 1.3. Current status: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022

The latest report on the progress of the SDGs was published in 2022. And the released results and analysis are overall far from positive. It is a unanimous conclusion that the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by armed conflict, including in Ukraine, the rise in gas and oil prices and a number of environmental “incidents” have greatly affected the progress thus far in a negative way. The information presented in the report is based on the latest available data (as of June 2022) on selected indicators in the global indicator framework1 for the SDGs. Some of the key takeaways on the status/challenges for each goal are presented below, via direct extracts from the report itself:

Goal 1. No Poverty : More than 4 years of progress against poverty has been erased by COVID-19; Rising inflation and impacts of war in Ukraine further derail progress number of people living in extreme poverty in 2022. The pre-pandemic projection was 581 million, with current projection: 657-676 million

Goal 2. Zero Hunger : To reduce stunting in children by 50% by 2030, annual rate must double, Ukraine crisis triggered food shortages for the world's poorest people

Goal 3. Good health and well-being : 22.7 million children missed basic vaccines in 2020- 3.7 million more than in 2019, Tuberculosis deaths rise for the first time since 2005, The Covid-19 pandemic Infected more than (mid-2022) (2020-2021) worldwide and led to 15 million deaths (end 2021) Disrupted essential health services: 92%of countries halted progress on universal health care

Goal 4. Quality education : Entrenched inequities in education have only worsened during the pandemic, missed over half of in-person instruction; COVID-19 pandemic global learning crisis has deepened a 147 million children in 2020-2021

Goal 5. Gender Equality : Gender-responsive budgeting needs to be strengthened, it would take another 40 years for women and men to be represented equally in national political leadership at the current pace, Women accounted for 39% of total employment in 2019, but 45% of global employment losses in 2020.

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation: Meeting drinking water, sanitation and hygiene targets by 2030 requires a 4x increase in the pace of progress

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy: International financial flows to developing countries for renewables declined for a second year in a row, impressive progress in electrification has slowed

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth : global unemployment to remain above pre-pandemic level until at least until 2023, Global economic recovery is further set back by the Ukraine crisis,

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure: Global manufacturing has rebounded from the pandemic but LDCs are left behind, Passenger airline industry is still struggling to recoup catastrophic losses

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities: Pandemic has caused the first rise in between-country income inequality in a generation; Global refugee figure hits record high

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities: Leaving no one behind will require an intensified focus on 1 billion slum dwellers

Goal 12. Responsible production and consumption: 13.3% of the world’s food is lost after harvesting and before reaching retail markets, our reliance on natural resources is increasing.

Goal 13. Climate action: Climate finance falls short of $100 billion yearly commitment, energy related CO2 emissions increased 6% in 2021, reaching the highest ever level; Rising global temperatures continue unabated, leading to more extreme weather

Goal 14. Life below water: Increasing acidification is threatening marine life and limiting the ocean’s capacity to moderate climate change, 17+ million metric tons of plastic entered the ocean in 2021

Goal 15. Life on land: Biodiversity is largely neglected in covid-19 recovery spending, 133 Parties have ratified the Nagoya Protocol which addresses access to genetic resources and their fair and equitable use.

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions: A record 100 million people had been forcibly displaced worldwide (may 2022), corruption is found in every region.

Goal 17. Partnership for the goals: Rising debt burdens Internet threaten developing countries’ pandemic recovery, internet uptake accelerated during the pandemic. In 2021, Foreign direct investment rebounded to $1.58 trillion, up 64% from 2020.

The conclusion is that the events of the last two years have had a negative impact on the progress of the SDGs and efforts must be made to counteract and mitigate, if we are to reach the targets and have a chance at securing a sustainable and safe environment for the future.

Lesson 2: Critique of the Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development goals have been used as a roadmap to sustainability in the last 7 years. Serving as a guide to for state policies, business and personal conduct, their objective is to set targets and be a driver for change. Many claim that the SDGs are the imperfect, but still the best reflection of the existing complexities of the world and our impact, that has been done thus far. And it is exactly these “imperfections” that are the topic of scrutiny and criticism.

In fact, according to the Economist, already in 2015, “detractors argue that the breadth is at odds with the need to prioritise. The Economist describes the SDGs as so broad and sprawling as to,” …amount to a betrayal of the world's poorest people.”

Unfortunately, with the 2030 Agenda and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, world leaders have still not managed to move beyond the binary world view that the world should be made up of the developed world (that's "us" - Europe and North America) and all the others that are still "developing". Such an understanding of development assumes only one possibility of 'real' development, one that approximates our own. It is still a view of the world through the neoliberal lens of economic growth and economic development (Gobbo, 2016). The objectives could mean a shift towards equal partnerships that allow learning from each other, but in reality, their discourse is once again based on the separation of developed and underdeveloped in the typical economic paradigm.

Key points of criticism:

The targets

There is quite a wide-spread critique regarding the targets, undelaying each Goal. “For example, the Copenhagen Consensus Centre has led an initiative to conduct cost-benefit analysis on the SDG targets, highlighting that efforts to achieve some of the targets would be ‘poor value for money’ and suggesting that either they should be changed or dropped entirely (Lomborg 2014).” The lack of precise designation of the financing and how it is to be done, has proven to be a serious obstacle. In fact, according to the World Bank as published in the “WBG’s most comprehensive costing study, Beyond the Gap, estimates that meeting the infrastructure-related SDGs, plus infrastructure-related climate change mitigation, will require investment equivalent to 4.5–8.2 percent of low- and middle-income countries’ aggregate GDP per year during 2015–30. 5. In individual countries, however, especially low-income countries, investment needs can represent a substantially larger share of GDP.”

In addition to that, as per Philip Alston, there is no explicit link to specific human rights. Although connections can be made, it can be claimed that these links are not sufficient.

The indicators and the SDG index

There is a multilevel issue with the indicators. Although their objective is to guide and track progress, that have not been able to do so. According to reports, they do not fully encapsulate concepts, they leave room for contestation and interpretation and they do not cover anything that is not obviously tangible.

The SDG Index is one of the other points of contestation. According to Hickel, “the countries with the highest scores on this index are some of the most environmentally unsustainable countries in the world.” This is due to the fact that good performance on the goals related to development (which are most of them), can grant a high score, even if performance on sustainability is low. This is the case in a number of developed countries such as Sweden or US, both of which reportedly have “unsustainable levels of environmental impact”. In addition to that, the University of Leeds has reportedly published data, supporting exactly the thesis that high-ranked countries actually have extremely high levels of use of resources, pollution, etc.

This problem is heightened by the fact that most indicators do not take into account international trade, and the data does not reflect for instance production of an EU company that has outsourced to a developing country. This leads us to the issue of data.

Insufficient or incorrect data

In order to track the progress on the Goals, data from all states is required. This data has to be provided in a timely manner, has to be complete and accurate. However, this is not the case in reality. Data is missing in countries, that require the most efforts. According to a report published by Bali Swain, “there isn’t a single five-year period since 1990 where countries have enough data to report on more than 70 percent of MDG progress (UN Independent Expert Advisory Group 2014). More worryingly, about half of this data is based on firm country-level surveys; the rest are comprised of estimates, modelling and global monitoring”. Data is missing, outdated and unreliable. The “grey economy” is not reflected, corruption practices and illegal trade, forced labour, etc are also not reflected.

The language of the Goals

In 2015, Easterly, who is overtly critical of the Goals, stated that the SDGs answer the question of what should be done, but do not provide answers on “how?” and “who”. This suggests that knowing what needs to be done, does not provide the solution and without concrete responsibility distribution, all will remain unactionable. Furthermore, as the SDGs are non-binding and allow selection of goals implementation and state-by-state alterations of the targets, together with individuals’ responsibility, there is not enough pressure to act. And the reality is that without sufficient pressure, and relying only on cooperation will not bring the needed results. Unfortunately, this can already be observed by the insufficient progress made on the Goals, as briefly discussed in the previous lesson.

The paradox of resources

Researcher Rene Suša (2021) similarly claims that the core of the sustainable development goals involves a fundamental paradox: namely, sustainability and development as we know it simply are not compatible. We all know we live on a physically limited planet, but we still want to keep functioning within a system that is based on the model of unlimited growth. The concept of sustainability should thus be focused on what exactly is it that we want to last, what we want to make sustainable. The language of SDGs suggests the answer to this question seems to be that we want to maintain the socioeconomic structures that we enjoy today. This however, is not possible on a planet with finite resources. If we, on the other hand, look at how other parts of the world (apart from the Western world) understand and interpret sustainability, we might see the development too in completely new light. For example, many indigenous peoples define sustainability as having the ability to survive, being able to sustain oneself. For them, sustainability is not a term that describes the continuation of economic growth rates, but rather describes a way of life that enables you to stay alive on the long run. This seems like a simple concept, however, this is something that our system, and indeed the language of SDGs, clearly lacks.

Philip Alston

Philip Alston, the outgoing UN Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights (Alston, 2020) has been one of the main critics of the SDGs. According to him, one of the main problems with Goals is “their reliance on the flawed World Bank’s international poverty line (IPL) of $1.90 a day as a barometer of poverty, which he rightly judges to be too low a level to support a life of dignity consistent with basic human rights (Alston, 2020, p. 4). In his final report in 2020, he says that even “if the SDGs are met, billions of people will still face serious deprivation as the poverty line represents at best ‘a bare subsistence’” (Alston, 2020, p. 10). Perhaps the most crucial point of his criticism is that the SDGs call for economic growth, whilst acting against climate change. Economic growth, inequal distribution of resources and insufficient action towards policies that can be beneficial, have been the key drivers both for the negative impact on the climate and for the adverse effects on the poor. He further calls for recalibration of the SDGs. And he is not the only one. Numerous publications suggest the need for a change in approach, which has been strengthened by the pandemic and its effects.